Visa Rejected: Why India Denied my Entry

On the stakes & repercussions of Black internationalism.

Today was meant to be the day that the 22 students enrolled in my short-course at the National Institute of Design in Ahmedabad, India began working on their final projects. Entitled “Afropresentism: Indigenous Technologies and Temporal Rebellion,” the elective I was going to teach was the most enrolled course in the university’s Open Elective “Cultures of Care” program. To quote the course description I had put together:

“Hegemonic technologies’ dependence on bloodshed and exploitation have been rendered permissible through coercive justifications that position the wounding of colonial subjects as the ‘inevitable’ cost of connection. Considering the foundations to computer coding systems laid by ancient divination systems– from Yoruba Ifa, to Hindu Agnicayana – this course proposes Afropresentism as a reparative, pan-Indigenous intervention. Merging Black quantum temporality with recipes of ritual, this course aims to invite those wounded by the motherboard in all of its encoded machinations of dehumanization into a terrain where embodiment, in its most deeply-rooted materialization(s), is the ultimate hack.”

In an unfortunate turn of events, however, I am not in India. My visa application to travel to Ahmedabad was denied not once, but twice (with a third application stuck in bureaucratic limbo, 7 days into what is meant to be a 72-hour response window)–in what I’ve come to gather is likely a politically-motivated rejection.

When the NID Open Electives team reached out to me in July, I was at BlackStar Film Festival in Philadelphia. I was there to speak on a panel with Jazmin Jones and Chica Andrade called “Black on the Internet” and earlier that day I watched what was arguably one of my favorite films of the whole festival – “A Litany for Survival: The Life and Work of Audre Lorde.” There’s a part of the film that documents Lorde’s time guest lecturing at a school in Mississippi, and I remember feeling my own internal metrics of success pivoting towards that kind of experience as a goal post as I watched the archival footage of her there. It was nothing short of surreal to come back to where I was staying later that *same* day, opening up my inbox, and seeing an invitation to lecture in Gujarat. I was practically in tears when I called my grandpa to tell him the news – it was going to be my first time traveling to India, and the first thing my grandpa said was that this trip would be the final puzzle piece in the Afropresentism manifesto/book I’ve been sitting on all these years.

There’s a part of me that wanted to believe in the harmlessness of my own intentions. I wanted to go to Gujarat and connect with the Siddi (East-African descendent) communities there. I wanted to think about what Pan-Africanism looks like in that context, how casteism and anti-Blackness are in relationship to one another. It admittedly still feels grandiose to deduce that the reason I wasn’t granted entry into India was because of these intentions registering as far from frivolous in the eyes of the state. In retrospect though, I suppose it makes sense that my application to teach a course on “temporal rebellion” and the colonial implications of techno-states wouldn’t exactly fare well in the eyes of one of the world’s most technology-dependent empires . . .and my most recent post on here, “Afterlives of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade,” probably didn’t help my case either.

“SHOBANA SHANKAR: Many Africans in different parts of the Continent, curious about Indians’ lives, have asked me what caste is like, what it means to experience caste. In some contexts, for example, in Kenya, the question came from observation. In Nigeria, on the other hand, this question was driven by curiosity based on what people had heard and read. In other places, as in Senegal, this question has had local significance, as castes exist there as well. The Senegalese scientist Cheikh Anta Diop, in 1967, wrote that “the study of the caste system in India holds a wealth of lessons: it allows one to judge the relative importance of racial, economic, and ideological factors.” Known for his Afrocentric scholarship, Diop’s proposed African study of India—in a history of precolonial African civilizations—shows that the Afrocentric study of race and difference he was developing was complex, sophisticated, and profoundly global—hardly the simplistic reactionary work that many critics tried to make Afrocentricity out to be. The burdens Africans writing precolonial African history faced differed somewhat from the ones Indian historians faced, but, after independence from European colonization, this was a common priority and one that found Africans and Indians deeply interested in each others’ pasts. This necessarily meant grappling with caste and race as forms of difference in comparative, coexistent, and contrasting relationships.” – from “BLACKNESS AS SOLIDARITY/ IDENTIFICATION AGAINST CASTEISM AND RACISM IN “SOUTH INDIA” in the Funambulist Magazine: https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/the-subcontinent/blackness-as-solidarity-identification-against-casteism-and-racism-in-south-india

Visas function first and foremost as political screening mechanisms: designed to scrutinize and filter who and what moves into the nation-state’s sociospatial domain.

In all of my years of traveling with an American passport, I have never had a visa rejected. The same can not be said of the years before I was naturalized as a U.S. citizen – a shift in geopolitical access whose privileges are not lost on me (it’s worth noting that India’s visa application asks a question about whether your citizenship is by birth or by naturalization). There is a particular arrogance that those of us who bear Western passports grow accustomed to moving freely in the world with, though – the assumption that visas are mere formalities, part of a robotic procedure of rubber stamps. In reality however, visas function first and foremost as political screening mechanisms: designed to scrutinize and filter who and what moves into the nation-state’s sociospatial domain.

I am not naïve to the political repercussions of publicly engaging in work that is critical of the tech industry’s e-colonialism, or the stakes of organizing around what tech reparations will look like on a global scale. Historically, this is the exact kind of work that has been rigorously censored and surveilled. When I was curating programs at The Africa Center back in 2019, one of the series I did was about Black cultural workers who were forced to live in exile or had their mobility restricted on account of their internationalism – like Paul Robeson, who went from representing the U.S. in dozens of countries, to having his passport revoked for 8 years.

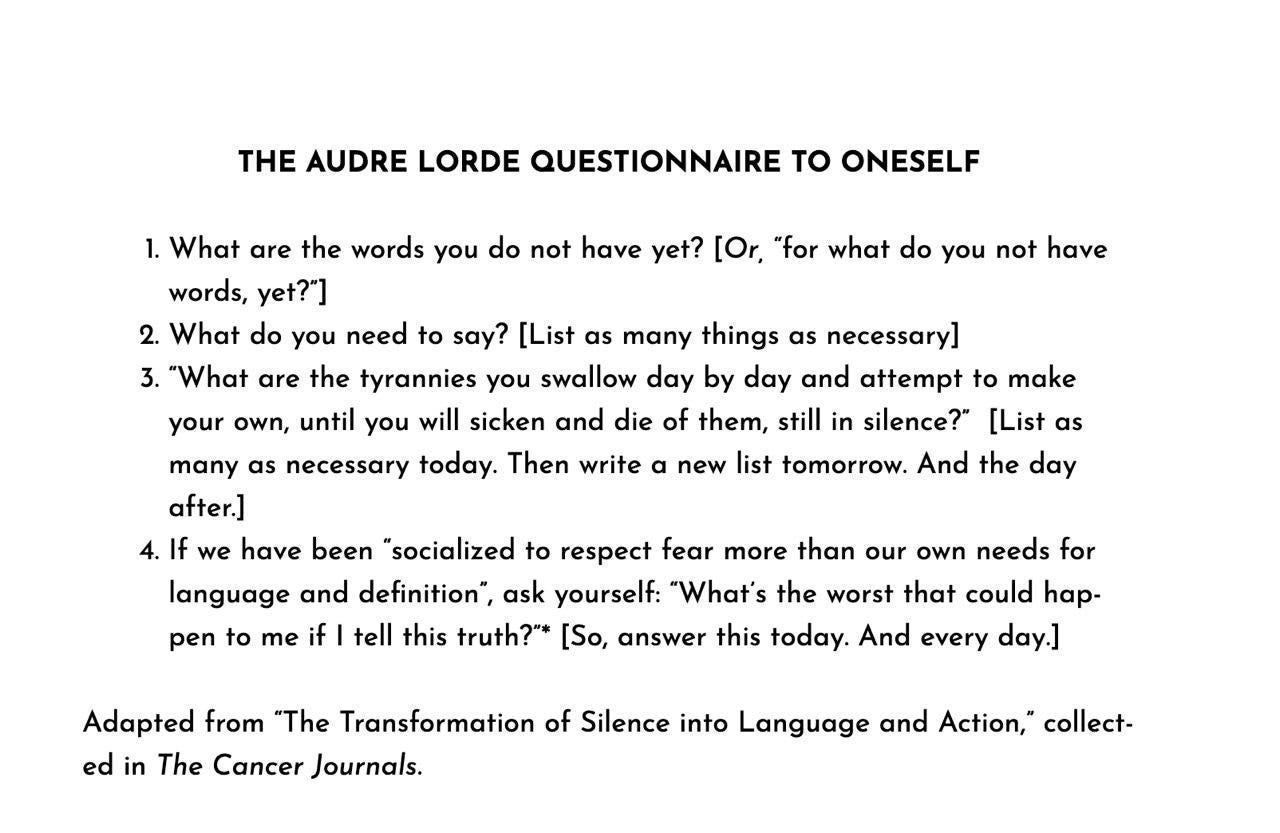

The stakes of even sharing about this experience publicly are not lost on me either – many of the academics who’ve faced similar rejections have opted to remain silent on their experiences in the hopes of not being permanently banned from future entries. That being said, sharing this felt necessary to do for a number of reasons. For one (as I’ve referenced often), the Audre Lorde Questionnaire to Oneself insists on naming the tyrannies you swallow day by day and that is an ethos I try my best to live by. Secondly, though, it feels important to be transparent about these very real political repercussions amidst a rising climate of Americans/Westerners fantasizing about just leaving the country in response to the election. As someone who is invested in internationalism not just in theory, but in practice, this form of romanticized political exile is one that I fear is not only potentially futile, but also threatens to put people in more harm than they are cognizant of. As much as I grieve the excitement I felt about going and lecturing in India, there’s a part of me that wonders what would have happened had I actually made it into the country and gone about my work without adequate infrastructure in place to shield me from graver political repercussions. Considering the rise of surveillance – trust that governments are arguably far more logistically advanced in their international solidarities to one another than we can conceive of – I hope that my own testimony of derailment can serve as a reminder for anyone else who works beyond & between borders to remain equal parts steadfast and cautious.

Yours in Radical Love,

Neema

this was a sobering read. i live & work between borders myself, and consider visa processes to be the bane of my life. you put words to an experience i’ve never known how to describe — i’ve conveniently called it ‘bureaucratic racism’ but have never felt like that term exactly cuts it. the stakes, the surveillance, and the constant sense of precarity, all of which are selectively applied, is really the system working exactly as it was designed to. this essay feels deeply personal to me — thank you for writing it!

ps. your work, and the concept of indigenous technologies and temporal rebellion, intrigues me to no end and i’d love to read/listen to anything you’ve discussed on the topic!

"there’s a part of me that wonders what would have happened had I actually made it into the country and gone about my work without adequate infrastructure in place to shield me from graver political repercussions." that paaart doe. Thank you for letting us know, and love your mind and analysis.